6 Apr 2020

The Ox: The Last of the Great Rock Stars

This month sees the publication of an authorised biography of John Entwistle entitled The Ox: The Last of the Great Rock Stars. It’s authorised by John’s first wife Alison and his son Christopher and is dedicated to them both – “for their trust and so much more”.

Our friend – and John’s too – journalist and writer Chris Charlesworth has written an honest and very fair review of The Ox on his excellent blog site Just Backdated and has kindly given us permission to reproduce it here. You can read more of Chris’s fascinating blogs at Just Backdated by clicking the link here. But first, The Ox . . .

THE OX: THE LAST OF THE GREAT ROCK STARS.

THE AUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY OF JOHN ENTWISTLE by Paul Rees

In 1990 John Entwistle spent two months in the region of Connemara on the west coast of Ireland where fierce winds coming off the Atlantic soon blew away any traces of last night’s old red wine. Here, in a stone house that was once the home of an archbishop, he began to write his life story, in longhand on A4 lined paper. He never finished the task and it remained unpublished during his lifetime but the tenor of what he wrote, in equal measure amusing, cynical and bitter, hangs over this biography like a dark thundercloud.

For all his wealth, acclaim and success John Entwistle was not a contented man. His dissatisfaction stemmed from issues he never felt able to enunciate, and it saw him retreat into himself, chasing his demons in ways that did him no good at all: booze, drugs, women, bad diets, reckless shopping sprees and an obstinacy that translated into denial. Many interviewees for this book – and they include both his ex-wives and son, as well as many musician friends – all seemed incapable of confronting him about these matters simply because, in his dealings with and without The Who, his natural instinct was always to avoid confrontations.

All of this contributes to a deep, persistent melancholia in the life of John Entwistle as conveyed by former Q editor Paul Rees. Less conspicuous than his colleagues in The Who but no less fascinating, Entwistle remained a distant, reserved figure to many, a character trait reinforced by the high profile antics of Pete Townshend, Roger Daltrey and Keith Moon. In this way, his story echoes what might be termed ‘The Bassists’ Curse’ – to be undervalued, unfulfilled and frustrated – and along with much else this led indirectly to his death at the relatively young age of 57.

While the The Who itself and the other three members have inspired books aplenty, Entwistle has until now lagged behind. The dilemma facing biographers of individual group members is in separating their subject from the group, and, with Entwistle’s peculiar nature only aggravating the situation, it is no surprise that the book suggests there were two Johns – John of The Who, and John of The Home. The former is the well-known Ox with the spider emblem around his neck, dapper, on the left of the stage, motionless save for fingers a blur on the long necks of his various basses, a rock star who dives eagerly into all the temptations that his calling offers him. The latter, however, is seemingly hewn from the same oak as The Kinks’ ‘Well Respected Man’. Off stage John Entwistle invariably behaves like an old-fashioned gentleman, well turned out, well spoken, and well mannered, a well-to-do professional man who lives his life by routines and loves a plate of fish and chips. The rot sets in when the two Johns start to merge.

The 344-page book is divided into three parts, the first about John’s early years, the second about The Who and his role within it, and the third his sad, ultimately tragic decline as Townshend and/or Daltrey put The Who on hold, leaving their brilliant bass guitarist to drift aimlessly. It came about after Rees wrote a profile of Entwistle for Classic Rock magazine for which he interviewed Alison, John’s childhood sweetheart and first wife, and Christopher, their son. The acquaintance made, Alison and Christopher co-operated with Rees when he proposed a full scale biography, and it is clear from its pages that their testimony, along with that of Maxene Harlow, John’s American second wife, was crucial to his research. Alison and Christopher also handed over John’s own text, enabling him to quote from it at will, and this helps the book enormously.

The result is very readable, leaning more towards the fate of the overindulged, hedonistic rock star and his troubled life than the music he created. Those looking for an insight into Entwistle’s extraordinary bass technique will be disappointed; although Rees heaps plenty of praise on John’s extraordinary skills, he hasn’t spoken to other bass players about how John did what he did. A handful of musicians express their admiration for John’s work too, but there is no attempt to analyse it, Rees having evidently concluded that to do so would decelerate the book’s pace.

John Entwistle’s early life was far from comfortable. An only child, he was 18 months old when his parents separated. He took an instant, everlasting dislike to his mother’s next partner and money was tight, which might explain why when he became rich he insisted on a preposterously high standard of living that would forever strain his finances. A naturally gifted musician, he inherited his talents from his parents and took lessons on the piano, then brass instruments and finally taught himself to play bass guitar because he liked the sound of Duane Eddy’s records. He took pleasure in making his first bass and thereafter immersed himself in the instrument, its makes, models and modes of amplification. His introduction to Townshend and, later, Daltrey, more or less tallies with all the other Who books I have, and The Who’s story is told – yet again (!) – in a breezy, competent fashion that differs from the rest only in that it benefits from John’s wry observations recorded in the text he wrote himself.

It is no secret that they didn’t get on personally, and Rees spares no blushes in detailing the various fall outs. Daltrey doesn’t come out if it well, a bit of a grumpy old bugger; Townshend is usually in a world of his own, a surprisingly absent presence in the book; and Moon is as mad as a box of frogs, though it is the drummer with whom Entwistle bonds most easily, the pair sharing a love of practical jokes and disorderly behaviour. The impression is given that Entwistle often provoked Moon in this and that he felt it was his duty to protect him, as if Keith was the little brother John never had. Moon’s death clearly affected Entwistle more than he let on. “I saw vulnerability in John when Keith died,” says manager Bill Curbishley. “There was something taken away from him that couldn’t ever be put back.”

A recurring theme up to this point is The Who’s precarious finances which didn’t stabilise until Tommy was a success. When real money arrived at last, all bar Daltrey were reckless spenders and Entwistle maintained his profligate ways until the very end, stockpiling possessions galore that filled his houses to the brim, even Quarwood, near Stow On The Wold in Gloucestershire, the gigantic pile he bought in 1976 and owned until his death. Rees contends that John’s collection of bass guitars was the biggest in the world.

The crux for Entwistle came when Townshend brought the curtain down on The Who for the first time at the end of 1982. ‘To Entwistle, Townshend’s decision was a personal affront,’ writes Rees. ‘Initially, he was despairing, but soon enough this turned to a seething, burning resentment.’ “He would have toured and toured,” adds Curbishley. “That was his life.”

Already dark, Entwistle’s life from this point onwards becomes a calamity of almost epic proportions. Outwardly buoyant but inwardly furious, he increases his consumption of all the poisons, chief among them brandy and cocaine, he’d happily ingested in The Who, confident that his physical strength can withstand it all. For a long time, far longer than Moon, this was the case but as we move from the eighties into the nineties it becomes clear that the only difference between Entwistle and Moon was that it took him an extra 24 years to kill himself.

Serially promiscuous, John divorces Alison – who is heartbroken – and takes up with Maxene, a nice LA girl who before long realises that keeping up with John will kill her and joins AA, only for this to put a wedge between them. She is followed by Lisa, a bad LA girl, who matches John glass for glass and toke for toke and who is ultimately blamed, at least by Christopher, for killing his father. “It was Lisa that truly fucked him up,” he says. “And I hate her for what she did to him.”

John’s tours with his own bands are covered extensively – as, throughout, are his solo recordings – but there is a nagging sense that he’s flogging a dead horse. The only respite from this descent into hell – as the red tops would have it – are those occasions when Townshend and Daltrey elect to reform The Who for various reasons, not least among them to shore up their finances. But no sooner is Entwistle back in the black than he’s on the phone to Harrods, his preferred retailer.

Entwistle played his last show with The Who at London’s Royal Albert Hall on February 8, 2002, but it was comforting to be reminded that the last show he played with them in America – a country he loved – was in October 2001 at Madison Square Garden, the Concert For New York to recognise the firemen who died in 9/11, and that it was a triumph, one of the group’s best ever in the post-Moon era.

As is well known, John Entwistle died alongside a good time girl on June 27, 2002, in Las Vegas from a heart attack induced not by the previous night’s consumption but by a lifetime of indulgence. There was a bit of unpleasantness in the aftermath, much of it caused by Lisa, but in a poignant Epilogue we join Alison and Christopher at a garden party in 2018, the pair of them sharing memories with old Who retainers of the man they remember as husband and father. “He was a very silly boy, but I loved him for years and years, and I didn’t stop loving him,” says the girl who knew him long before he was John of The Who. She preferred John of The Home and was, after all, just 13 when that 14-year-old boy began courting her.

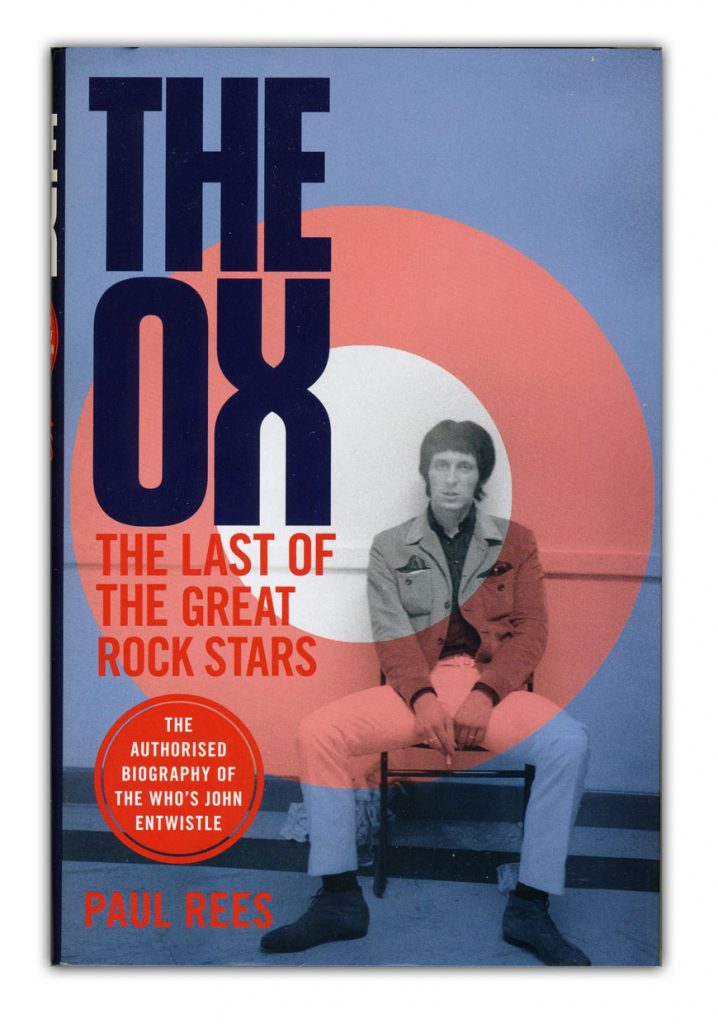

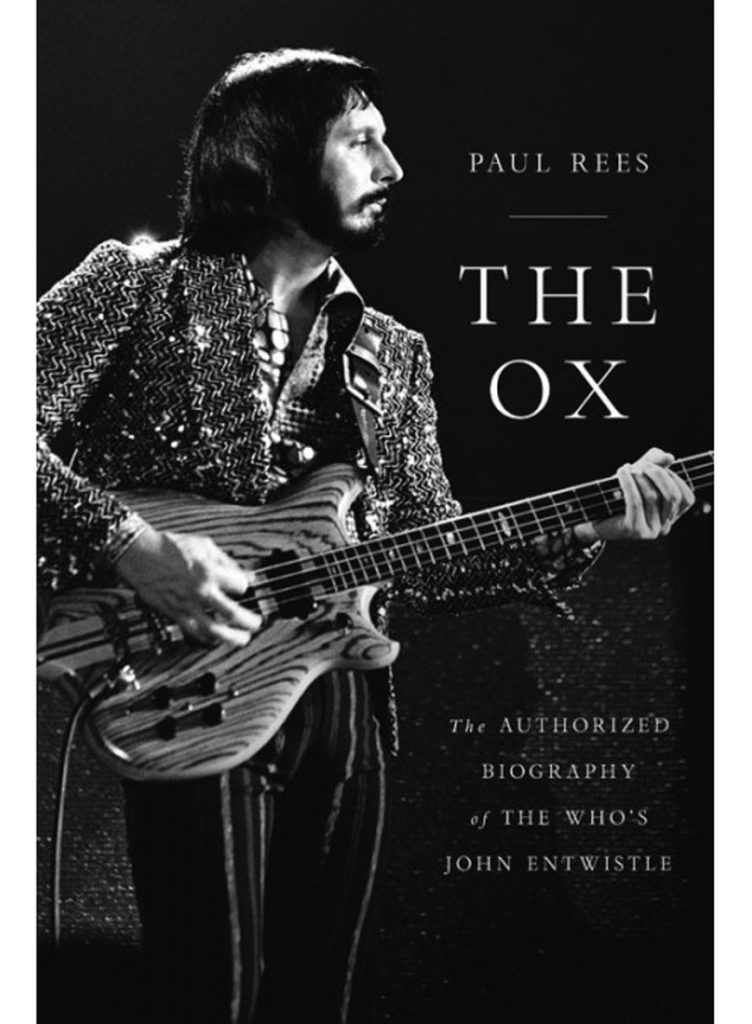

Finally, the book is well indexed, lacks a discography and I’m not too keen on the cover which looks a bit washed out to me. The cover of the US edition, below, is far better.

Purchase Links:

Long overdue.

Absolutely the best bassist of the rock era. I’m so looking forward to reading this biography.

Super review. I am looking forward to the read!

Long live The Ox!

Hmm, bit difficult these days, Keith.

The solo he played at the first Teenage Cancer Trust concert at the Albert hall was a master class on bass guitar and the smile on his face when Roger asks ‘how many notes was that, John?’ is unforgettable Thanks for the memory, John

Thanks for posting this review. I saw John live plenty of times, both with The Who and with his back-up band on the ‘solo’ tour(s). I saw one of the last live shows he ever did, at BB Kings (Times Square). He will be sorely missed, and never replaceable.

Looking forward to reading this book!

Well,John and Keith are long gone,but can we see Pete and Roger and

the others at the “ONE WORLD UNITED AT HOME concert ?

It´s a WHO(world Health Organisation)Event !!

Sorry,silly name-joke !

Thomas (Berlin,Germany)

Saw John’s solo tour in 1975. He was brilliant and a great gentleman to the musicians around him. He stood in the wings and watched Joe Walsh’s entire set. God bless you, John.

His master bass class course was a classic too. He explained that he took up the bass because it was bigger and longer than the guitar – more phallic.

I don’t collect autographs, I collect handshakes, and I shook John’s hand at the dump known as Park West, in Chicago.

Read this book last month. Very good.